During the past few months, executives from virtually every kind of company - from autos, to tech equipment, to financials - have invoked the "we've been hit by a perfect storm" excuse as to why they are underperforming recently provided expectations. The beauty of the perfect storm excuse is that it deflects accountability.

No doubt, there is some truth to the fact that a confluence of factors have come together to negatively impact their business. The questions are "why is it a surprise" and "is this really as bad as it gets".

The confluence of factors often provided: deleveraging, consumer recession/demand collapse, lameduck presidency, housing collapse, stock market collapse, credit market collapse sure sounds like a perfect storm!

Other than the lameduck presidency, upon which I place virtually nil weighting for our present circumstance, these factors are all correlated. However, what our "blameless" business executives don't realize is that the perfect storm is not today, it was the boom times that were the perfect storm. Instead of calling it the Perfect Storm, I'm going to refer to it as the Suckers' Rally of 2004-2007.

Let's take a look at the Suckers' Rally, who is to blame, and why it was so damnable.

Congress is owed a huge dollop of blame, as is the Fed, borrowers, and all the usual sensationalist suspects. Everyone caused it. But especially the Fed. If we can agree that we went through a credit orgy, we have to point fingers most directly at the fathers of currency and credit: The Federal Reserve of the United States.

Let's step back and think about what it means to take on debt?

Debt is basically the process of taking from your future to spend or invest today. Conversely, saving is the process of taking from today to set aside for spending or investing in the future. That's what most people do not think about: debt is taking from your future. It ought to be a fairly attractive purchase or investment to entice you to take from your own future.

Our government encourages taking on debt in many, many more ways than savings, despite some nice things like 401-Ks and IRAs. One of its primary methods for encouraging borrowing is the tax deductibility of mortgage interest for individuals and the tax deductibility of all forms of interest for corporations (I first talked about this in a frighteningly prescient post in August of 2006). The Fed, through its Fed Funds and Discount rates also has provided a remarkably subsidized borrowing rate for much of the past two decades and has strongly encouraged banks to increase their leverage ratios until very recently.

In fact, while the Fed has increased the Fed Funds rate to something close to reasonable a couple of times, I cannot think of a time since the late 80s when the Fed has offered anything close to a punitive rate. You'd think, in order to offset some of the excesses that will obviously be created during times of cheap and easy money, it would need to occasionally offer a punitive rate. The Fed, however, seems quite one-sided in its price of money equation. This is obviously stupid as it basically is the equivalent of driving by only utilizing a balance of speeding and occasional short bursts of shifting to neutral before putting your foot back on the gas, but never using the brakes. Seems like just a matter of time before something gets out of hand. Most people would recognize that quickly.

Not our Fed, it seems.

These factors combined to create a huge increase in credit in the economy. As a percentage of GDP, credit nationally is about 360% and growing (page 13 in the presentation or this link), which is off the charts compared to history (at the peak of the Great Depression, largely because GDP declined by 46%, it reached 250% or so). Historically, 200% was high. Mind you, GDP is about $14 trillion per year (but shrinking). Therefore, every 100% decrease in credit as a percentage of GDP means contracting credit by $14 trillion dollars (or an entire year's economic output). Scary, but I digress.

Frankly, my personal belief is that the availability of inappropriately easy, unnaturally cheap credit is to blame for virtually every problem that ails us right now. The implication of this huge boom in readily available, subsidized credit was to create a spending orgy. We just took and took from our future to spend more and more in the here and now.

Businesses took these spending signals in exactly the way we should expect them to: they expanded capacity to meet the new "demand" not realizing that it was not sustainable demand. Rather, it was the future’s demand being brought forward to today – we can only take from the future for so long, so that type of “demand” is inherently limited in its ultimate scope and sustainability. That means that the capacity expansion of American business over the last decade was in response to a false signal: an unsustainable spending boom.

We saw this expansion in obvious areas like housing, but also in things like a huge boom in retail shopping outlets, an explosion in eating out (which is a more expensive way to deliver calories than cooking in), a huge boom in new car purchases, a huge boom in luxury goods "demand", a huge boom in leisure travel, etc., etc. Each of these booms leads down the supply chain to explosions of "demand" for inputs like steel (and thusly iron ore and coal), power, oil, timber, labor, etc., etc. Businesses sized up to serve this “demand”.

Just imagine what this means: Virtually everything in our society expanded to meet a demand that was inherently temporary. What a giant, giant period of malinvestment caused directly by the policies of our Federal Reserve and governmental leaders!! The frightening corollary to this is that because recent demand was taken from the future, the future's demand will now be "falsely" lower than it otherwise would have been, perhaps mistakenly sending the opposite signal. The implications for fallow capacity are scary.

In any case, I think there are a lot of fingers that ought to be pointed, but none more directly than at the Fed. Sadly, they’ve caused the problem yet we’ve also charged them with fixing the problem.

The "solution" to our unnatural explosion in credit that's being proposed? More credit! Our government has decided to replace all of the vanishing private sector borrowings (i.e., deleveraging) with public sector borrowings (i.e., levering up!).

I suppose the best analogy is taking a heroin addict to a meth clinic, but without any real supervision or understanding of the impact on the otherside.

A horrorshow of inflation seems like a virtually certainty to me, but only after a period of deleveraging caused deflation. Helicopter Ben has all but guaranteed a classic Helicopter Drop of cash. He is Charlie Munger's Man With a Hammer (to the man with a hammer, every problem looks like a nail). Deflation is Bernanke's nail. He has trained his entire life for this moment. I assure you he will not stop swinging his hammer until the nail's head has disappeared into the wood and the wood has a permanent hammer imprint pounded firmly into it.

Going back to the beginning of this post: why is it a surprise? and is this as bad as it gets?

The answer to the former is that while it's not a surprise to me, I think it is perfectly reasonable that most businesspeople were hoodwinked into believing false demand signals. The incentives for believing it are too powerful and the ability to recognize and dodge it is too rare.

As to the latter, I'm afraid not. We are not even remotely dealing with the root cause of this problem: too much leverage. Instead, we are adding new borrowed money to replace the bad borrowings of the past. The issue with these new borrowings (financed by We The People) is that the only credible way to pay them off will be the printing press. The problems that come with a massive inflation will be new and fun...

Believe in Liberty. Think for youself. But listen to me. - T.T. Buffett, Investment Linebacker -Tu Ne Cede Malis

Saturday, December 27, 2008

Boycott Over

Ever since Congress and our President approved the TARP legislation, I have been boycotting posting to my blog. It is dispicable and has turned into the unrestrained catch-all, bailout bill. So much bad policy and decision making has been enacted by our leaders since then that I cannot help but talk about it.

I hereby begin posting my rants again.

I hereby begin posting my rants again.

Monday, September 29, 2008

Congress grows a pair - staring into the abyss

Well, today was a day you only get to experience a few times in your life. Crazy. And you know what, I'm kind of proud of Congress. Seriously. If you've read my prior posts, you know that I've been against this "bailout" (read: subsidy) since the beginning. Before I get into my thoughts on the bailout, I think it is worth explicitly stating that the S&P 500 was down about 9% today on the Wachovia news and the spate of European financial failures (B&B, Fortis, and Hypo), with final capitulation after The House showed some balls and voted down this embarrassment.

That said, I never actually expected them to have the rocks to vote nay. I promise you, it was not easy to say "no". In this case, saying no legitimately means putting the global financial system at risk but doing so because it is what is best for the very long term health of the system.

Having seen a few movies with scenes of a heroin detox process depicted, this seems fairly analogous. As the druggie gets past the state where heroin is fun and into the stage where it is depressing and painful, he knows that his best option is to seek help. But seeking help sucks. He'll often almost get help several times just to succumb to his addiction in ever more painful ways. Going through a detox appears akin to a near death experience. And while it is clearly the better outcome in the long run, it always appears to be a horrifically painful fate in the nearer term. I think that is why so often it requires an external intervention. Someone generally forces the druggie into rehab. This normally happens after they hit a series of new personal lows and start stealing from friends and family to feed the habit.

Well, it's pretty obvious that the debt induced orgy we've been on for the past three decades is our drugs and alcohol.

A little debt is like having a few beers: it's great as long as you have some self-control and don't feel like you can't live without a few beers or the number of beers you need to have in order to enjoy yourself is constantly growing. Before you know it, alcoholism manifests itself as a sort of gateway drug and you're a heroin addict. Well, that's how we got from real money buyers allowing their bond portfolios to be repo'd in order to generate a few extra bips to AIG writing CDS on CDO-squareds.

A little debt is like having a few beers: it's great as long as you have some self-control and don't feel like you can't live without a few beers or the number of beers you need to have in order to enjoy yourself is constantly growing. Before you know it, alcoholism manifests itself as a sort of gateway drug and you're a heroin addict. Well, that's how we got from real money buyers allowing their bond portfolios to be repo'd in order to generate a few extra bips to AIG writing CDS on CDO-squareds.This is one of those cases where I think Congress was better lucky than smart. They voted this down for all the wrong reasons, but at least the conclusion (not that it is truly concluded) was the right one. They voted this down because in our bicameral system, our Founding Fathers decided the House would have to run for re-election every two years. If the bailout bill was up for vote this time last year, I suspect it passes. But with a national election only five weeks away and their constituents against the bailout by a ratio of something like 9:1, passing the bailout was career suicide and these guys have their own addiction that they can't seem to kick: power that comes with office. The reality is, I don't think these guys have any clue that they may have just set off a daisy chain of deleveraging that was already underway, but now has the potential to accelerate in an ugly fashion.

I suspect that the run on the money markets re-accelerates (mind you, it never stopped, which nobody is really talking about). Money market funds that are not purely invested in US Treasuries often serve as a short-term funding source to businesses via things like commercial paper (CP). CP is used by Main Street businesses to manage working capital sort of like a line of credit. The CP cycle allows them to keep very little cash on hand but do things like meet payroll, which is a somewhat lumpy cash event for most businesses. Obviously, as a few businesses miss payroll, folks aren't going to be happy. But frankly, for Main Street businesses, it is a temporary problem. CP is not their life-blood; it's merely a convenience.

For Wall Street businesses and many large'ish banks, CP is part of their lifeblood. It is a funding source that they explicitly rely on. As such, when Lehman went bust, as one of the larger issuers of CP, it actually caused a few money market funds - including the oldest and largest Reserve Fund, to break the buck. This led to lots of money market fund investors to actually look at what their funds were investing in and they freaked out! Other than Treasuries, these funds are often a veritable murderers row of borrowers: Lehman, Goldman, Morgan Stanley, Fannie, Freddie, B of A, Citi, BNP Paribas, ING, ANZ, UBS, off balance sheet vehicles like SIVs, etc., etc., ad nauseum.

When money market investors actually looked at that line-up of underlying investments and realized they'd indirectly lent their cash to the global financial system, everyone ran for the door at once. But the problem is money market funds are really the only natural buyers of CP assets and as all the non-Treasury money market funds shrank at the same time, there were no natural buyers for CP assets and therefore money market funds could not meet their redemptions. Thus money market funds had to freeze redeeming investors which caused an even greater freak-out than breaking the buck. This freezing of some money market funds led to investors in other money market funds to redeem before their fund was frozen as well, effectively leading to runs on all kinds of non-Treasury money market funds.

Most money market investors think of these funds as cash alternatives (my Schwab account, for instance, actually labels my investment in money market funds as "Cash"). Not being able to get your "cash" pisses people off and the redemptions start flying.

So, this self-feeding redemption frenzy actually served as a non-traditional run-on-the-bank. As banks that rely on CP have their old CP loans mature (every month or so), they cannot issue new CP to pay-off the maturing loans. It is just like having an abnormal number of depositors leave at the same time: it causes the bank's liability structure to explode. I imagine that the Federal Home Loan Bank system is overflowing with borrowing requests right now in order to offset the CP evaporation, thus putting the entire system on pins and needles.

This was the state of the market two Wednesdays ago just prior to the Treasury's bailout announcement. At the same time as that announcement, the Fed set up a few programs that would allow money market funds to get liquidity and would guarantee the value of the funds. However, with yesterday's ballsy vote by the House, even with those guarantees, we are back to where we were which is to say we are Staring into the Abyss.

The Bailout:

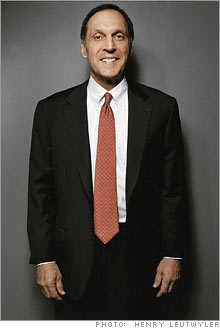

Hammerin' Hank Paulson is a man I respect a ton. He's in an awful, awful position. The ultimate lose/lose. But I feel like he's been a bit misleading about one thing: The Hammer continues to state that the root cause of the problems in the financial sector are housing and the related illiquid securities (for our purposes, we'll just call those securities "ABS", which is a bit broad). That is false. Those are symptoms of the root cause. The root cause is two fold:

1) too much leverage;

2) bad underwriting.

That really is a toxic combination as the each of the factors magnifies the problems of the other one. So, in my mind, any bailout plan that does not address the real root cause is not what we need and is a distraction from the end goal.

The Treasury's plan, in fact, actually rewards the bad behavior. We are protecting companies from the reality of too much leverage by buying their poorly underwritten assets at premium prices. This is a subsidy, plain and simple. And it's dumb.

If we collectively decide that it is too societally expensive to allow massive failures and we want to instill some calm amongst depositors, then some plan is needed. Thus, if we are going to put We The People's capital at risk, we absolutely must attack the core problems and begin healing. The detox must happen. The problem clearly cannot be put off again, because we may just end up overdosing and killing ourselves (if we haven't already).

So, I'd propose an alternate plan that allows companies to fail from an equity holder and non-depositor lender standpoint:

First: credit ratings agencies will be forced to compete and the current government authorized oligopoly will be loosened with an agency to monitor existing/approve new ratings agencies. Ratings scoring will be standardized and apples to apples across asset classes. The issuer will continue to pay for ratings, but the ratings agencies will have to defer 20% of their revenue to an insurance pool with a five year vesting. In any given one, three or five year period that their aggregate forecasts vary from expected outcomes by more than two standard deviations, some amount of the deferrals are forfeit. In extreme cases, fines could be levied as well. Any forfeit revenue will go to support certain aspects of the regulatory regime. Executive compensation of approved ratings agencies will be subject to the same terms outlined below for bankn executives.In sum, we force leverage down, transparency up, accountability up, and thus underwriting standards up. This improves confidence and soundness and provides a base to begin to grow from again. From a legislator's perspective, it protects depositors (consitituents), punishes poor business decisions, improves incentives, protects tax-payers, and limits similar situations from re-emerging in the future.

Second: banks have five years to take leverage to no more than 7:1 if the asset mix stays somewhere close to history. Leverage needs to be defined, but I might start by saying that it should be defined as delta adjusted notional exposure of long assets offset by 50% of the delta adjusted notional exposure of hedges. There will still be some risk-based element to the assets that are allowed to be owned. Leverage would be allowed to max at 9:1 if only super high quality assets were owned, as determined by the regulator/ratings agencies.

Third: FDIC expands its insurance level to $250,000 and heretofore, that level is indexed to inflation.

Fourth: during that five year period, any and all FDIC insured banks or thrifts that the pertinent regulator deems at serious risk would be subject to a similar takeover structure as AIG. The government will come in, provide a senior line of credit, cram down the entire capital structure below depositors, replace management if they ran the bank when the problems occurred, receive a massive warrant package, and set a time line for disposition via sale or IPO. These rules must be clearly stated so that depositors know they can depend on them and they must be consistently applied so that lenders and owners can operate in an environment that has some amount of predictability and standardization.

Fifth: During that initial five year period and beyond, for any FDIC insured institution (or insitution involved in the capital markets as a counterparty to an FDIC insured institution with more than $10 billion of notional counterparty exposure), employee compensation in excess of $2 million per year, set to inflation, would be deferred on an even four year vesting schedule (in year one you'd get $2 million, at the end of year two, you'd get 1/4 of the deferred comp, etc.). If the government has to implement an AIG-type plan, all deferred comp is forfeit and goes to the benefit of the FDIC's insurance fund. There is no employment vesting. So, the money is yours, free and clear, as long as your bank/institution does not fail (as defined by the AIG-type takeover) within four years of your last paycheck. This is not at all a limit on compensation, it is merely a recognition that if you are going to rely on a government subsidy for your operations, you need to be incented to behave in a way that minimizes long-term failure.

Sixth: Transparency to the public/depositors must improve somehow.

Finally, the government should immediately loosen ownership restrictions on private equity buyers taking stakes in banks, but force them to over-equitize initially.

What does this mean? I'll give the quick answer here. Regardless of whether my ideas or any other are implemented (including the Treasury bailout), we are going to witness the great deleveraging of our time. Thus, there will be a one-time, painful readjustment in values in order to reflect less available, more stringent, more expensive leverage.

Historically, an 80% Loan to Value ("LTV") loan on a house has been a reasonably safe loan. The buyer's 20% was enough skin in the game to keep him/her/them honest even if it turns out the house price was a bit high. Lenders rarely lost money. A big part of this was that houses were historically appreciating assets (unlike most cars, for example) and thus the lender's margin of safety was growing in two ways: 1) every month the borrower paid back some principal on the mortgage, improving the LTV; and 2) over time the value of the home increased, also improving the LTV.

However, everything seems to have suddenly changed. Borrowers' behavior is less predictable - they are willingly defaulting on their mortgages much more often (even those that had 20% down). Further, home prices are declining. Now, from an aggregate standpoint, that same 80% LTV mortgage seems substantially less attractive to the lender. Their margin for error seems to actually be shrinking rather than growing.

So, what will the rational lender do?

1) delever their balance sheet: in response to the volume of bad loans and the increasingly transitory nature of deposits, banks are going to delever in order to feel they can safely operate. Lenders and owners will require it. Reducing blow-up risk is key. So, fewer loans will be available in aggregate unless we capitalize a bunch of new banks or existing banks raise a ton of equity;

2) raise standards: You're going to make sure the people you loan to are highly unlikely to default - so credit quality will rise, which weeds out certain borrowers;

3) raise your price: You're going to charge wider spreads to your funding costs in order to compensate you for the higher risk you perceive that is associated. This has a depressing effect on asset prices as the cost of acquiring assets rises, all else being equal;

4) lend at lower LTVs: You're going to make borrowers put more of their own skin in the game which a) gives you more protection in case they default and in case asset values continue to decline; and b) makes the borrower less likely to default since he/she/they have more to lose. This will have the effect of weeding out borrowers who haven't saved up enough to be able to put up a bigger chunk of money.

Collectively, those four factors will have a depressive effect on any asset classes that have historically been acquired with borrowed money (LBO targets, real estate, etc.) in order to reflect less competition amongst buyers, to compensate the buyers for the increased cost of borrowing, and to generate attractive returns to the equity. This deleveraging spiral obviously has the ability to feed on itself until one day, it stops.

My guess is it will correct too far and at that point, the man with cash will be in an a once-in-a-lifetime position to profit. Buy assets when the provide reasonably attractive unlevered returns for the risk assumed. Levering those returns would just be gravy.

This is a time to sit and wait. Then when big opportunities come, and they will come if this volatility and deleveraging keeps up, swing hard.

-TTB

Wachovia goes down on the same day Congress grows a pair - welcome to the Dark Side

Hhheewwwwwww [sound of a long exhale].

Hhheewwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww

Hhhhhhheeewwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwwww

Wow. What to make of it all? These two topics (Wachovia and the bailout) deserve two distinct posts. This one is going to be Wachovia.

First off, I hate (love) to say it, but I was spot on again. Wachovia goes down. And, yes, this is a bank failure. Taking out the third or so largest bank in the United States for $1/share plus paying the government Twelve f'ing Billion dollars to insure you against losses in the event the losses on a pre-identified $312 billion portion of Wachovia's asset portfolio exceed $42 billion? That implies there could be another $54 billion of losses in that portfolio. Really? I mean, wow. Folks, that is a failure. Don't let anyone tell you otherwise. The FDIC doesn't tend to post non-failure bank mergers on their website. It's a failure. Period.

And why did it fail? Major credit agencies were poised to downgrade the Dubya Bee if it didn't raise capital ASAP. As I discussed the other day, private lenders had already implicitly downgraded Wachovia by taking their credit to junk-like spreads after the FDIC's actions around WaMu rightfully freaked them out. My post (linked above) from last Friday was prescient enough that I'll go ahead and quote the pertinent section right here:

In that first post of 2008, I said that the failure of WaMu would be more important than the failure of the GSEs. I believe that proved out today, though most people still don't realize it. When WaMu was seized by the FDIC then flipped to JP Morganington Mutual Chase Stearns & Co, it had at least one odd unintended consequence. It absolutely screwed senior creditors who certainly assumed that their loan was secured by the assets and liabilities of the bank operating companies as well as the HoldCo assets. Instead, the FDIC used its authority under a seizure to rip the assets from the bond holders and sell them to JPM. In fact, the FDIC turned a $1.9 billion profit on the flip!So, Wachovia "failed" because the government decided it could not allow the bank to really "fail", if that makes sense. The writing was on the wall: losses were mounting, equity was depressed to levels that limited a capital infusion, buyers had been trained by the FDIC and the markets to just wait and the price will keep declining, credit funding costs were massively non-economic, ratings agencies were about to drop the hammer, and the media was all over the story leading to a potential for a lack of confidence driven bank run. In all, the whole thing was totally foreseeable and, I suspect, an excellent deal for Citi assuming they have managed to deal with their own problems. I actually trust Vikram Pandit more than any of the major Wall Street CEOs (including Glorious Jamie Dimon and LaLaLaLaLloyd Blankfein). He was the most aggressive about raising fresh capital back when that was doable, he's not married to the company and its legacy problems, he was early in grasping that the problems the industry is facing are big, and he is well regarded for his focus on understanding risk and return. That said, so much of what is happening these days is outsripping expectations that it's certainly possible Citi has their own problems elsewhere, but my guess is Citi is fine (as an aside, Citi is the only bank that I own, though it's not a big position).

If you happened to be a senior lender to the next-weakest large financial institution, like, say, Wachovia, it turns out that you may not have enjoyed witnessing your colleagues in the world of lending to banks getting publicly gutted by the Feds.

So, what happened today to Wachovia? Well, it wasn't good. Wachovia CDS spreads blew out. As noted in the link, a standard CDS contract is quoted as the cost over swaps of a five year senior obligation. Wachovia closed Thursday (just prior to the WaMu gutting) at about 695 bps over (no up front points). It closed Friday at 40 points up front and 500 bps running! Doh! So, if we assume swaps are about 3.5% today and we just evenly divide up the 40 up front points over five years (8%/year), we are looking at Wachovia's current senior funding costs at about 16.5% per annumn (3.5% + 5.0% + 8.0%). Ouch! Hopefully they don't need to tap the credit markets in the near future!

Also, this is a classic unintended consequence of the no new short selling rule: if you want to short WB, the SEC has pretty much forced you to use CDS. Idiot Cox.

Some how evil speculators and Wall Street derivatives traders will be blamed for "manipulating" Wachovia's CDS costs, but the reality is it simply reflects the new failure paradigm that the FDIC defined through its actions for large bank failures. Charging a higher cost to lend to financial institutions is absolutely the rational thing to do. As regulators continue to manipulate the natural order of things, the more frequently and painfully these unintended consequences will pop up.

Luckily for Wachovia, if they need to shore up their capital base, they can always just issue stock.

Or...maybe not. Wachovia's stock was down about 40% today to $9/share. Interestingly, if you look at the presentation JP Morganington Mutual Chase Stearns & Co. sent around last night on the WaMu acquisition, they break out bucket by bucket how they came up with the $31 billion write-off they took on WM's portfolio (page #15), they wrote off another $8.2 billion or about 13% of the remaining Option ARM portfolio. They also wrote-off another 17% of the HELOC & LOC portfolio in addition to other broad asset category write-offs. In total, JPM wrote down WaMu's asset portfolio by about 15%.

Those are enormous write-offs and, if apples to apples, would imply devestation for Wachovia. Even if Wachovia's asset base (page #4), which also has huge Option ARM ($125 billion) and HELOC/LOC ($58 billion) portfolios out of a total $477 billion asset base is of better quality than WaMu, it's only going to be modestly better and WaMu had been more aggressive in its write-offs than WB even before the JPM takeover. I first discussed WB's balance sheet issues vis a vie WM back on August 6th. Given a nearly half a trillion dollar asset portfolio, Wachovia's market cap is just over $20 billion, so the margin for error is unusually small.

Another unintended consequence of the JPM/WM deal is that if you are a potential acquiror of WB equity (in whole or part), what's the rush? The longer you wait, the more the situation develops, the lower the price seems to go, and the more desperate the Feds become for private sector help. The government's perspective surely is that a bank Wachovia's size cannot be allowed to "fail". Another issue is that Wachovia is so big, the government really cannot allow it to be swallowed by another large bank. So, that means it would be split up. By delivering WaMu on a silver platter to JPM, the FDIC has shown that it is more than happy to kill a bank prematurely if it facilitates an orderly transition. Of course, that "order" is real only if viewed in a vacuum. Each one of these government manipulations seems to spawn now uncertainties and unintended consequences.

Given the small market cap vs. the magnitude of the potential problem taken in conjunction with the cost of debt financing, Wachovia's clock is ticking. They will do one of the following, and soon: 1) prove everyone wrong and show their asset quality is such that it does not need to be marked down much more (btw, auditors will definitely look at the WM/JPM transaction for valuation comps); 2) sell itself; or 3) fail and be sold by the FDIC. Frankly, I don't think there are any other alternatives given the impracticality of raising the necessary financing.

A final unintended consequence of WaMu's failure being such an orderly failure (no depositors were hurt) is that the media, which had been fairly restrained in an attempt to help avoid causing a self-fulfilling fear-based run on a bank, now has some cover to start reporting negative bank news before it becomes overwhelmingly obvious. In fact, the media seems to have taken off the gloves and decided no holds are barred. This NY Times article on Wachovia is a case in point. This sort of article did not used to get published by the mainstream media.

So, as I said, WaMu's failure is s scary thing. Creditors and owners of weak banks everywhere are rightfully nervous

I hope your boots were strapped on, because we are knee deep in it now.

It obviously begs the question: who's next? There are several obvious small banks to medium-small banks/thrifts like Bank United and Downey that are toast. I shared this link in early September and if you look at what has failed so far, we've really only just begun to make a dent in the list. Titans like Wachovia and WaMu were not even on the list. Those are the kinds of banks I'm most curious about. It seems to me that Regions Financial, Nat City, and Sovereign are all at risk. They are big enough to have CDS, they are big enough to catch media attention, they all clearly have problem loan books, and they all have important depositor bases. If I'm a big depositor at any of those three, I can't figure out why I'm staying. I know that Linda Lou at Regions has been my banker for all of my adult life and she assures me that everything is fine, but I suspect if you go ask Beauregard the Banker across the street at B of A whether they have been getting an abnormal amount of inflows from new depositors, the answer is an emphatic yes. As a depositor (ie, "lender") at Regions, that scares me. I'm walking.

Finally, and I'll touch on this is a follow-up post about Congress growing a giant pair today and voting against the bailout, but the credit markets broadly and CP markets specifically are in shambles and that's going to have a really negative impact on a number of financial institutions, medium-large banks certainly included.

You should be nervous. Things are bad.

-TTB

Friday, September 26, 2008

Where to Begin?

Washington Mutual failed last night. It wasn't even a Friday. Given how much I look forward to checking the FDIC website every Friday evening, it's with a small tinge of disappointment that I note WaMu failed on Thursday September 25th. That said, it is with a great deal of self-congratulatory arrogance that in the same above linked post, I also noted that WaMu was "probably still six or eight weeks out" from failing. That post was dated August 2, 2008. That was just under eight weeks ago. I'm not sayin', I'm just sayin', that's all... I also have been predicting that the catalyst for WaMu's failure would not be a traditional run on the bank, but a slow motion run on the bank by large depositors who a) have more to lose; and b) on average are more market aware and thus would be the most likely people to withdraw their deposits. In the last two weeks or so, the media has reported that $17 billion in deposits walked from WaMu, driven largely by large depositors.

I first predicted WaMu's failure in this blog back in mid-July. I started talking about it privately a few months prior to that. In fact, you'll note that the WaMu failure post was actually my first blog posting of 2008. That overwhelming sense that WaMu/SnaFu was toast and that nobody was focusing on it is what actually opened the floodgates for my blogging. Since then, everything that I've expected to happen (and some) has occurred.

Now, onto news. Effectively, JPM paid $1.9 billion to the FDIC and took a $31 billion write down as the cost of the acquisition (basically, $34 billion). They expect the WaMu transaction to add $2.4 billion in earnings in 2009 and then grow in the out years. That implies that JPM was able to acquire WM at 14x run-rate earnings. I suspect that WM contributes much more than that to JPM's annual earnings over time.

In that first post of 2008, I said that the failure of WaMu would be more important than the failure of the GSEs. I believe that proved out today, though most people still don't realize it. When WaMu was seized by the FDIC then flipped to JP Morganington Mutual Chase Stearns & Co, it had at least one odd unintended consequence. It absolutely screwed senior creditors who certainly assumed that their loan was secured by the assets and liabilities of the bank operating companies as well as the HoldCo assets. Instead, the FDIC used its authority under a seizure to rip the assets from the bond holders and sell them to JPM. In fact, the FDIC turned a $1.9 billion profit on the flip!

If you happened to be a senior lender to the next-weakest large financial institution, like, say, Wachovia, it turns out that you may not have enjoyed witnessing your colleagues in the world of lending to banks getting publicly gutted by the Feds.

So, what happened today to Wachovia? Well, it wasn't good. Wachovia CDS spreads blew out. As noted in the link, a standard CDS contract is quoted as the cost over swaps of a five year senior obligation. Wachovia closed Thursday (just prior to the WaMu gutting) at about 695 bps over (no up front points). It closed Friday at 40 points up front and 500 bps running! Doh! So, if we assume swaps are about 3.5% today and we just evenly divide up the 40 up front points over five years (8%/year), we are looking at Wachovia's current senior funding costs at about 16.5% per annumn (3.5% + 5.0% + 8.0%). Ouch! Hopefully they don't need to tap the credit markets in the near future!

Also, this is a classic unintended consequence of the no new short selling rule: if you want to short WB, the SEC has pretty much forced you to use CDS. Idiot Cox.

Some how evil speculators and Wall Street derivatives traders will be blamed for "manipulating" Wachovia's CDS costs, but the reality is it simply reflects the new failure paradigm that the FDIC defined through its actions for large bank failures. Charging a higher cost to lend to financial institutions is absolutely the rational thing to do. As regulators continue to manipulate the natural order of things, the more frequently and painfully these unintended consequences will pop up.

Luckily for Wachovia, if they need to shore up their capital base, they can always just issue stock.

Or...maybe not. Wachovia's stock was down about 40% today to $9/share. Interestingly, if you look at the presentation JP Morganington Mutual Chase Stearns & Co. sent around last night on the WaMu acquisition, they break out bucket by bucket how they came up with the $31 billion write-off they took on WM's portfolio (page #15), they wrote off another $8.2 billion or about 13% of the remaining Option ARM portfolio. They also wrote-off another 17% of the HELOC & LOC portfolio in addition to other broad asset category write-offs. In total, JPM wrote down WaMu's asset portfolio by about 15%.

Those are enormous write-offs and, if apples to apples, would imply devestation for Wachovia. Even if Wachovia's asset base (page #4), which also has huge Option ARM ($125 billion) and HELOC/LOC ($58 billion) portfolios out of a total $477 billion asset base is of better quality than WaMu, it's only going to be modestly better and WaMu had been more aggressive in its write-offs than WB even before the JPM takeover. I first discussed WB's balance sheet issues vis a vie WM back on August 6th. Given a nearly half a trillion dollar asset portfolio, Wachovia's market cap is just over $20 billion, so the margin for error is unusually small.

Another unintended consequence of the JPM/WM deal is that if you are a potential acquiror of WB equity (in whole or part), what's the rush? The longer you wait, the more the situation develops, the lower the price seems to go, and the more desperate the Feds become for private sector help. The government's perspective surely is that a bank Wachovia's size cannot be allowed to "fail". Another issue is that Wachovia is so big, the government really cannot allow it to be swallowed by another large bank. So, that means it would be split up. By delivering WaMu on a silver platter to JPM, the FDIC has shown that it is more than happy to kill a bank prematurely if it facilitates an orderly transition. Of course, that "order" is real only if viewed in a vacuum. Each one of these government manipulations seems to spawn now uncertainties and unintended consequences.

Given the small market cap vs. the magnitude of the potential problem taken in conjunction with the cost of debt financing, Wachovia's clock is ticking. They will do one of the following, and soon: 1) prove everyone wrong and show their asset quality is such that it does not need to be marked down much more (btw, auditors will definitely look at the WM/JPM transaction for valuation comps); 2) sell itself; or 3) fail and be sold by the FDIC. Frankly, I don't think there are any other alternatives given the impracticality of raising the necessary financing.

A final unintended consequence of WaMu's failure being such an orderly failure (no depositors were hurt) is that the media, which had been fairly restrained in an attempt to help avoid causing a self-fulfilling fear-based run on a bank, now has some cover to start reporting negative bank news before it becomes overwhelmingly obvious. In fact, the media seems to have taken off the gloves and decided no holds are barred. This NY Times article on Wachovia is a case in point. This sort of article did not used to get published by the mainstream media.

So, as I said, WaMu's failure is s scary thing. Creditors and owners of weak banks everywhere are rightfully nervous

I hope your boots were strapped on, because we are knee deep in it now.

-TTB

I first predicted WaMu's failure in this blog back in mid-July. I started talking about it privately a few months prior to that. In fact, you'll note that the WaMu failure post was actually my first blog posting of 2008. That overwhelming sense that WaMu/SnaFu was toast and that nobody was focusing on it is what actually opened the floodgates for my blogging. Since then, everything that I've expected to happen (and some) has occurred.

Now, onto news. Effectively, JPM paid $1.9 billion to the FDIC and took a $31 billion write down as the cost of the acquisition (basically, $34 billion). They expect the WaMu transaction to add $2.4 billion in earnings in 2009 and then grow in the out years. That implies that JPM was able to acquire WM at 14x run-rate earnings. I suspect that WM contributes much more than that to JPM's annual earnings over time.

In that first post of 2008, I said that the failure of WaMu would be more important than the failure of the GSEs. I believe that proved out today, though most people still don't realize it. When WaMu was seized by the FDIC then flipped to JP Morganington Mutual Chase Stearns & Co, it had at least one odd unintended consequence. It absolutely screwed senior creditors who certainly assumed that their loan was secured by the assets and liabilities of the bank operating companies as well as the HoldCo assets. Instead, the FDIC used its authority under a seizure to rip the assets from the bond holders and sell them to JPM. In fact, the FDIC turned a $1.9 billion profit on the flip!

If you happened to be a senior lender to the next-weakest large financial institution, like, say, Wachovia, it turns out that you may not have enjoyed witnessing your colleagues in the world of lending to banks getting publicly gutted by the Feds.

So, what happened today to Wachovia? Well, it wasn't good. Wachovia CDS spreads blew out. As noted in the link, a standard CDS contract is quoted as the cost over swaps of a five year senior obligation. Wachovia closed Thursday (just prior to the WaMu gutting) at about 695 bps over (no up front points). It closed Friday at 40 points up front and 500 bps running! Doh! So, if we assume swaps are about 3.5% today and we just evenly divide up the 40 up front points over five years (8%/year), we are looking at Wachovia's current senior funding costs at about 16.5% per annumn (3.5% + 5.0% + 8.0%). Ouch! Hopefully they don't need to tap the credit markets in the near future!

Also, this is a classic unintended consequence of the no new short selling rule: if you want to short WB, the SEC has pretty much forced you to use CDS. Idiot Cox.

Some how evil speculators and Wall Street derivatives traders will be blamed for "manipulating" Wachovia's CDS costs, but the reality is it simply reflects the new failure paradigm that the FDIC defined through its actions for large bank failures. Charging a higher cost to lend to financial institutions is absolutely the rational thing to do. As regulators continue to manipulate the natural order of things, the more frequently and painfully these unintended consequences will pop up.

Luckily for Wachovia, if they need to shore up their capital base, they can always just issue stock.

Or...maybe not. Wachovia's stock was down about 40% today to $9/share. Interestingly, if you look at the presentation JP Morganington Mutual Chase Stearns & Co. sent around last night on the WaMu acquisition, they break out bucket by bucket how they came up with the $31 billion write-off they took on WM's portfolio (page #15), they wrote off another $8.2 billion or about 13% of the remaining Option ARM portfolio. They also wrote-off another 17% of the HELOC & LOC portfolio in addition to other broad asset category write-offs. In total, JPM wrote down WaMu's asset portfolio by about 15%.

Those are enormous write-offs and, if apples to apples, would imply devestation for Wachovia. Even if Wachovia's asset base (page #4), which also has huge Option ARM ($125 billion) and HELOC/LOC ($58 billion) portfolios out of a total $477 billion asset base is of better quality than WaMu, it's only going to be modestly better and WaMu had been more aggressive in its write-offs than WB even before the JPM takeover. I first discussed WB's balance sheet issues vis a vie WM back on August 6th. Given a nearly half a trillion dollar asset portfolio, Wachovia's market cap is just over $20 billion, so the margin for error is unusually small.

Another unintended consequence of the JPM/WM deal is that if you are a potential acquiror of WB equity (in whole or part), what's the rush? The longer you wait, the more the situation develops, the lower the price seems to go, and the more desperate the Feds become for private sector help. The government's perspective surely is that a bank Wachovia's size cannot be allowed to "fail". Another issue is that Wachovia is so big, the government really cannot allow it to be swallowed by another large bank. So, that means it would be split up. By delivering WaMu on a silver platter to JPM, the FDIC has shown that it is more than happy to kill a bank prematurely if it facilitates an orderly transition. Of course, that "order" is real only if viewed in a vacuum. Each one of these government manipulations seems to spawn now uncertainties and unintended consequences.

Given the small market cap vs. the magnitude of the potential problem taken in conjunction with the cost of debt financing, Wachovia's clock is ticking. They will do one of the following, and soon: 1) prove everyone wrong and show their asset quality is such that it does not need to be marked down much more (btw, auditors will definitely look at the WM/JPM transaction for valuation comps); 2) sell itself; or 3) fail and be sold by the FDIC. Frankly, I don't think there are any other alternatives given the impracticality of raising the necessary financing.

A final unintended consequence of WaMu's failure being such an orderly failure (no depositors were hurt) is that the media, which had been fairly restrained in an attempt to help avoid causing a self-fulfilling fear-based run on a bank, now has some cover to start reporting negative bank news before it becomes overwhelmingly obvious. In fact, the media seems to have taken off the gloves and decided no holds are barred. This NY Times article on Wachovia is a case in point. This sort of article did not used to get published by the mainstream media.

So, as I said, WaMu's failure is s scary thing. Creditors and owners of weak banks everywhere are rightfully nervous

I hope your boots were strapped on, because we are knee deep in it now.

-TTB

Down Goes WaMu! Down Goes Wamu!

As I predicted, WaMu goes down. The FDIC technically seized it (creating a donut for WM shareholders) then immediately flipped the assets and liabilities of the bank to JP Morganington Stearns & Co. for $1.9 billion (paid to the FDIC). Very clean from the FDIC's standpoint. Very, very, very bad for creditors of WaMu HoldCo. Very bad.

Anyway, more on this and the fact that the bailout is BUSTED over the weekend. What a day, what a week!

Anyway, more on this and the fact that the bailout is BUSTED over the weekend. What a day, what a week!

Wednesday, September 24, 2008

The Overs Take it! (and how!)

For each of the last two weeks, the overs have taken it running away. I guess technically the failure of Fannie and Freddie two weeks ago (it seems like a lifetime ago!) don't qualify as depository institutions, but I'll make an exception. And while Lehman and AIG aren't perfect fits either, their epic failure combined with the failure of tiny Ameribank, Inc. in West Virginia certainly meets the intent of the rule.

I have an enormous number of thoughts about the Keystone Cops', I mean Hammerin' Hank and Helicopter Ben's, announcement about the reliquification of the global financial sector using We The People's money.

I can sum it up my views very briefly with the following statement: as long as they continue to expect any losses from this bailout, we know for a fact that the government intends to overpay for the mortgage assets! I can assure you the Street will hit that bid and hammer the Treasury over and over again with the worst assets at the wrong prices until the Treasury lowers its bid. Then the Street will pound the bid some more.

In theory, the taxpayers ought to be making a profit on this if we buy at reasonable prices (ignoring all of the unintended consequences) and it is an f'ing travesty that the implicit subsidy of the banking system which I've been railing on for years is becoming explicit.

We damned well better extract a pound of flesh.

The Hammer keeps saying that the root causes of this once "contained subprime problem" are falling housing prices and the resultant illiquid, depressed asset values that banks are carrying. That is fundamentally misleading. The root problem is too much allowable leverage by banks due to their falsely precise regulatory oversight and Fed backstop combined with bad to horrific underwriting practices. This reliquidifcation does absolutely nothing to address either of those issues.

Prediction: more pain to come, even it we shift who receives it.

Further prediction: before Treasie Mae and Feddie Mac can get this horrific foray into trickle down communism up and running, we run headlong into some other large problems.

I will have more thoughts on this in the coming days. Suffice it to say I think the whole thing is evil.

-TTB

PS: Don't trust a word from anyone at a bank, on Wall Street, or at a firm like PIMCO, Blackrock or TCW. They are all completely and utterly comprimised by this bailout. Wall Street and commercial banks all stand to sell assets to tax payers at inflated prices and investment management firms like PIMCO and Blackrock stand to be hired by Treasie Mae as external managers to run the process. I expect a thorough knob slobbing until this is over.

I have an enormous number of thoughts about the Keystone Cops', I mean Hammerin' Hank and Helicopter Ben's, announcement about the reliquification of the global financial sector using We The People's money.

I can sum it up my views very briefly with the following statement: as long as they continue to expect any losses from this bailout, we know for a fact that the government intends to overpay for the mortgage assets! I can assure you the Street will hit that bid and hammer the Treasury over and over again with the worst assets at the wrong prices until the Treasury lowers its bid. Then the Street will pound the bid some more.

In theory, the taxpayers ought to be making a profit on this if we buy at reasonable prices (ignoring all of the unintended consequences) and it is an f'ing travesty that the implicit subsidy of the banking system which I've been railing on for years is becoming explicit.

We damned well better extract a pound of flesh.

The Hammer keeps saying that the root causes of this once "contained subprime problem" are falling housing prices and the resultant illiquid, depressed asset values that banks are carrying. That is fundamentally misleading. The root problem is too much allowable leverage by banks due to their falsely precise regulatory oversight and Fed backstop combined with bad to horrific underwriting practices. This reliquidifcation does absolutely nothing to address either of those issues.

Prediction: more pain to come, even it we shift who receives it.

Further prediction: before Treasie Mae and Feddie Mac can get this horrific foray into trickle down communism up and running, we run headlong into some other large problems.

I will have more thoughts on this in the coming days. Suffice it to say I think the whole thing is evil.

-TTB

PS: Don't trust a word from anyone at a bank, on Wall Street, or at a firm like PIMCO, Blackrock or TCW. They are all completely and utterly comprimised by this bailout. Wall Street and commercial banks all stand to sell assets to tax payers at inflated prices and investment management firms like PIMCO and Blackrock stand to be hired by Treasie Mae as external managers to run the process. I expect a thorough knob slobbing until this is over.

Wednesday, September 17, 2008

Having just killed AIG, bloodthirsty media barron CNBC sets its sights on Morgan and Goldman

Have you noticed that CNBC seems to be creating self-fulfilling prophecies with each failure?

It always seems to begin with them quoting some unnamed source with a fairly innocuous statement like, "AIG is contemplating ways to raise capital." Next, CNBC will put that company's ticker symbol in emergency orange at the top of its screen on the rolling bar such that its stock price is highlighted every 30 seconds or so. Then, Charlie Gasparino will breathlessly and angrily tell us about what the rumors being mongered on The Street are about said company. Then the share price starts declining and credit spreads widen out a few hundred basis points. Finally, because all of these companies rely heavily on continuous access to short term funding sources for their daily survival, the death becomes almost self fulfilling as the company's alternatives for raising capital dwindle, its existing capital providers run for the hills, and the broad media becomes like a dog in heat and humps the company until its dead.

The fact that Morgan and Goldman are being attacked is as much a CNBC created problem as a problem created by the bogeyman...I mean, evil short sellers. Let's be clear, this is not a problem caused by short sellers or the media, this is a problem caused by a fundamentally flawed business model. Businesses that require access to short term leverage and invest in assets that may not be saleable at attractive prices in the short term have an inherent mismatch that leaves them constantly at risk. The business models are inherently fragile (particularly when levered as much as the investment banks are/were). Publicly traded guys may be in even more of a risky position since their stock price can work against them if they desperately need to raise capital. It is perfectly rational for capital providers to Morgan and/or Goldman to be nervous. They should be raising their prices, withdrawing their deposits, or moving the brokerage relationships. As I've said many, many times in the past, the basic blocking and tackling of i-banks and commercial banks is a commodity service. No hedge fund manager is getting paid to PB at Morgan. In fact, when Morgan's risk profile rises, the hedge fund manager is kind of getting paid to not PB at Morgan. Where's the upside?

This unwind will continue until financial institutions have delevered and changed their asset/liability mix to such an extent that their soundness is not in question.

If leverage going to be lower, if the asset side needs to be more liquid, and if the liability side needs a longer term-structure, I can assure you the price of money is going to rise. Period. Get ready for it. If you think you're going to need to borrow money in the coming few years, I recommend trying to do it now before the cost catches up with its inevitable future.

Anyway, AIG is dead. Ding dong. As I predicted in my post on AIG when people were talking about potential a "bridge loan" from the Fed but not contemplating brutal dilution/nationalization as a result, AIG got Paulsoned. I am stunned that nobody else saw this outcome coming. This was obviously the new standard. How could they possibly justify giving AIG a better deal than FNM and FRE? They couldn't. It seemed totally obvious to me that if the Feds got involved, the new methodology was nationalization.

Who knew that the US Treasury was really the world's largest LBO fund? Their sourcing edge is fantastic, they never enter a competitive process, and for some reason the targets always take their price. We may get out of this budget deficit yet! Just nationalize a few more world class insurance companies (We The People now own the three largest insurers in the world, since that's what FNM and FRE really are), flip them in five to ten years and...walla! No more deficit!

[as an aside, I'm short GS, LEH, JPM, WFC, WM and MS, so take my opinion with a grain of salt]

Tuesday, September 16, 2008

AIG - Imminent Doom

Having seen David Faber on CNBC say that the "private" market solution to AIG is definitively dead, we now look on at a potential government bailout of the insurance and investment behemoth.

I've handicapped the odds of a government intervention as 60%. So, that means 40% odds of an outright bankruptcy and likely zero recovery for shareholders. Within the 60 points of government intervention, I'd put 50 of them on a Fannie/Freddie type bailout, which means that equity holders get diluted into oblivian and sub-debt holders are at substantial risk. In fact, I'd suspect that the Fed loan would be super-senior to everything accept policy holders and thus everything in the capital structure would get crammed down and the profit motive of the institution will be questioned (a scenario where equity is diluted 80% but the company is worth less than if it remained private). The other 10 points of odds I'd place on a non-dilutive loan that effectively lets AIG continue to prosper and does not kill the current equity holders. In that scenario, AIG may be worth well over $20/share. So, if I probability weight the outcomes:

40% x $0 +

50% * $4 +

10% * $25 =

$4.50/share of probable value.

I'd demand a fair margin of safety to that given the risk of immediate and total loss. I'd buy at less than $1/share, hold below $2.25 and not want to be involved above that. [MY VIEWS SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS INVESTMENT RECOMMENDATIONS, JUST BACK OF THE ENVELOPE ANALYSIS]

I've handicapped the odds of a government intervention as 60%. So, that means 40% odds of an outright bankruptcy and likely zero recovery for shareholders. Within the 60 points of government intervention, I'd put 50 of them on a Fannie/Freddie type bailout, which means that equity holders get diluted into oblivian and sub-debt holders are at substantial risk. In fact, I'd suspect that the Fed loan would be super-senior to everything accept policy holders and thus everything in the capital structure would get crammed down and the profit motive of the institution will be questioned (a scenario where equity is diluted 80% but the company is worth less than if it remained private). The other 10 points of odds I'd place on a non-dilutive loan that effectively lets AIG continue to prosper and does not kill the current equity holders. In that scenario, AIG may be worth well over $20/share. So, if I probability weight the outcomes:

40% x $0 +

50% * $4 +

10% * $25 =

$4.50/share of probable value.

I'd demand a fair margin of safety to that given the risk of immediate and total loss. I'd buy at less than $1/share, hold below $2.25 and not want to be involved above that. [MY VIEWS SHOULD NOT BE CONSTRUED AS INVESTMENT RECOMMENDATIONS, JUST BACK OF THE ENVELOPE ANALYSIS]

Monday, September 15, 2008

AIG Hits for the Cycle: Downgraded by All Three Major Ratings Agencies in a Three Hour Span

Today was a big one on the richter scale. You don't get too many of these in your life, so I'm taking it all in while it is happening, painful as that may be. And the hits keep coming.

In addition to Lehman filing BK, the Dow dropping 500+ points (the S&P declined nearly 5%!), and Merrill being taken out for what was initially a 50+% premium and NOT f'ing BUDGING (it closed up $0.01 at $17.06) AIG is on the brink.

AIG is in real trouble. It is suffering from taking the wrong side of a massive, correlated bet on mortgage related assets (especially ABS CDOs) expressed via CDS. As these trades crater and create a hole in the middle of AIG's balance sheet, credit ratings agencies have threatened to downgrade AIG unless it raises funds to replenish that hole. AIG is letting on today that the size of its capital needs are somewhere between $40 billion and $75 billion. You know... pocket change.

The magnitude of AIG's potential capital shortfall combined with threat of downgrade of course has made the hole filling process much more difficult as the share price has cratered and credit spreads on AIG have launched out to distressed spreads. This has all but made raising capital via traditional means impossible. AIG is now contemplating selling some of its prized assets such as its aircraft leasing business, but a) comps are trading horribly (see ticker AYR) and b) it will take months to actually receive the cash from a sale that size.

So, AIG is in quite a bind. As a result, they asked the Fed for a $40-$50 billion loan, which it seems the Fed denied on the basis that AIG is not under the Fed's regulatory purview. AIG then managed to hoodwink the state of NY into allowing AIG to take its illiquid crap and use it as collateral to borrow $20 billion from its insurance subs. This is of course insanity as the policy holders are now being put at risk by a problem that has nothing to do with them or the entity with whom they have contracted (I smell.....lawsuits!). That of course does not solve anything as it just shuffles the losses around for a period of time. So, the Fed is apparently "encouraging" Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan to lead a consorsium in putting together a $70 billion (with a B) loan facility for AIG to tap (this of course is seperate and distinct from the cross collateralized $70 billion "Private Fed"/loan facility that 10 banks organized yesterday).

What I find just a remarkable "coincidence" about this new $70 billion facility is that it is being talked about a mere 24 hours after the Fed significantly expanded the acceptable collateral for its lending facilities. That expansion was of course a page A18 news event for the WSJ, basically lost in the commotion. However, the conspiracy theorist in me sees these two actions as highly connected. Basically, if JP Morgan and Goldman assemble this facility, my suspicion is they will take qualifying collateral from AIG, make a loan against that collateral at a modest spread to Fed borrowing rates, then take that collateral and post it to the Fed pocketing a largely risk free arb.

This of course is similar (though slightly different) to when the Fed allowed Bear to access it via JP Morgan as a conduit. The difference is a) the Bear deal was perfectly transparent; and b) JP Morgan didn't receive a spread, to the best of my knowledge.

Maybe I'm just seeing black helicopters, but it sure seems like a remarkable coincidence to me. This has Timothy Geithner's fingerprints all over it.

As an aside, I said when the Merrill deal was announced that this is the riskiest merger arb I've ever seen, so trading at a wide spread is perfectly rational. If somehow the MER/BAC deal breaks, Merrill is a zero and BAC may skyrocket. That's a dangerous deal to arb so the arbs are going to demand to get paid. The nearly $6 spread that exists today is a reflection of that. Ken Lewis today said that the break-up fee was "expensive" and intentionally so, but my guess is that he views the Merrill deal as a call option where the option price is the break-up fee. Probably a pretty rational approach, frankly.

In addition to Lehman filing BK, the Dow dropping 500+ points (the S&P declined nearly 5%!), and Merrill being taken out for what was initially a 50+% premium and NOT f'ing BUDGING (it closed up $0.01 at $17.06) AIG is on the brink.

AIG is in real trouble. It is suffering from taking the wrong side of a massive, correlated bet on mortgage related assets (especially ABS CDOs) expressed via CDS. As these trades crater and create a hole in the middle of AIG's balance sheet, credit ratings agencies have threatened to downgrade AIG unless it raises funds to replenish that hole. AIG is letting on today that the size of its capital needs are somewhere between $40 billion and $75 billion. You know... pocket change.

The magnitude of AIG's potential capital shortfall combined with threat of downgrade of course has made the hole filling process much more difficult as the share price has cratered and credit spreads on AIG have launched out to distressed spreads. This has all but made raising capital via traditional means impossible. AIG is now contemplating selling some of its prized assets such as its aircraft leasing business, but a) comps are trading horribly (see ticker AYR) and b) it will take months to actually receive the cash from a sale that size.

So, AIG is in quite a bind. As a result, they asked the Fed for a $40-$50 billion loan, which it seems the Fed denied on the basis that AIG is not under the Fed's regulatory purview. AIG then managed to hoodwink the state of NY into allowing AIG to take its illiquid crap and use it as collateral to borrow $20 billion from its insurance subs. This is of course insanity as the policy holders are now being put at risk by a problem that has nothing to do with them or the entity with whom they have contracted (I smell.....lawsuits!). That of course does not solve anything as it just shuffles the losses around for a period of time. So, the Fed is apparently "encouraging" Goldman Sachs and JP Morgan to lead a consorsium in putting together a $70 billion (with a B) loan facility for AIG to tap (this of course is seperate and distinct from the cross collateralized $70 billion "Private Fed"/loan facility that 10 banks organized yesterday).

What I find just a remarkable "coincidence" about this new $70 billion facility is that it is being talked about a mere 24 hours after the Fed significantly expanded the acceptable collateral for its lending facilities. That expansion was of course a page A18 news event for the WSJ, basically lost in the commotion. However, the conspiracy theorist in me sees these two actions as highly connected. Basically, if JP Morgan and Goldman assemble this facility, my suspicion is they will take qualifying collateral from AIG, make a loan against that collateral at a modest spread to Fed borrowing rates, then take that collateral and post it to the Fed pocketing a largely risk free arb.

This of course is similar (though slightly different) to when the Fed allowed Bear to access it via JP Morgan as a conduit. The difference is a) the Bear deal was perfectly transparent; and b) JP Morgan didn't receive a spread, to the best of my knowledge.

Maybe I'm just seeing black helicopters, but it sure seems like a remarkable coincidence to me. This has Timothy Geithner's fingerprints all over it.

As an aside, I said when the Merrill deal was announced that this is the riskiest merger arb I've ever seen, so trading at a wide spread is perfectly rational. If somehow the MER/BAC deal breaks, Merrill is a zero and BAC may skyrocket. That's a dangerous deal to arb so the arbs are going to demand to get paid. The nearly $6 spread that exists today is a reflection of that. Ken Lewis today said that the break-up fee was "expensive" and intentionally so, but my guess is that he views the Merrill deal as a call option where the option price is the break-up fee. Probably a pretty rational approach, frankly.

AIG Could Fail 48-72 Hours After a Ratings Downgrade

Wow. How do you let your business run on such a razor thin edge? This artThis article by the NY Times says that AIG will have to come up with $14-18 billion of cash upon a single step ratings downgrade. The article also states that a person "close to the firm" said AIG may survive a mere 48-72 hours if a downgrade were to occur. The implications of that are mindboggling. This is a world-caliber company.

I imagine Buffett is licking his chops. He runs the only other world-caliber re-insurer and the opportunity to either buy AIG on the cheap or take business from it while it languishes justify every dollar of capital he has kept close to the Omaha headquarters over the past six years. Has there ever been a greater investing genius - he warned us years ago about "financial weapons of mass destruction" (derivatives) and sold Freddie after it started expanding from its G-fee business. As equity markets ran up over these past few years, he has husbanded cash more and more aggressively and now it appears that Berkshire's time has come. Amazing.

I imagine Buffett is licking his chops. He runs the only other world-caliber re-insurer and the opportunity to either buy AIG on the cheap or take business from it while it languishes justify every dollar of capital he has kept close to the Omaha headquarters over the past six years. Has there ever been a greater investing genius - he warned us years ago about "financial weapons of mass destruction" (derivatives) and sold Freddie after it started expanding from its G-fee business. As equity markets ran up over these past few years, he has husbanded cash more and more aggressively and now it appears that Berkshire's time has come. Amazing.

Sunday, September 14, 2008

HOLY F'ING SHIT

Well, I'm not even going to try to link this. Just go to any news site. Let's just say that the future of the Western financial system has clearly taken a left turn. Regulation? Taxes? Inflation? Higher borrowing costs? These are all in our future.

In the past six months:

- Bear Stearns goes down

- Lehman goes down

- Merrill goes down

- AIG tells the Fed it needs a $40 billion loan in order to keep its credit rating (doesn't that mean it has already lost its rating...can you be Double A rated if you occasionally need a $40 billion short term loan to avoid a death spiral)

- Freddie Mac goes down

- Fannie Mae goes down

- Ten investment banks pool $70 billion to protect against bank runs

- The Fed offers to take equity...Equity...EQUITY as collateral. EQUITY!?!?!?! I mean, how long until hedge funds start shooting at the Fed balance sheet? I'm guessing it's a matter of days

Can I say that Ken Lewis has no balls? There's no way that Merrill doesn't open as a low teens or lower stock price on Monday and he pays $29/share. Helicopter Ben and his Boy Wonder Tim Geithner have their hands all over this.

I put in an order for $800 calls on gold on Friday and my order never hit. Ugh. Couldn't be more pissed about that.

Addition:

It seems absolutely clear to me that the $70 billion bank capital pool is in place to protect the next weakest player. I suspect Morgan Stanley and, to a lesser extent, Goldman Sachs are shitting their pants. This is a Morgan Stanley prop. And they are smart to do so. Without this, Morgan Stanley would be under attack on Monday. And, frankly, they may very well still be under attack. And if the attack happens fast enough and hard enough, it will weaken several of the other members of the liquidity pool.

Strap your boots on. Hope everyone is prepared to be a fully equitized buyer of assets going forward...

Barclays Pulls Out of Lehman Talks AND AIG Needs to Raise $30-$40 BILLION

"Nothing to see here. Nothing to see here. Don't worry, the 'subprime crisis' is contained. Keep moving. Nothing to see here."

Honestly, the guys who were trying to sell us this pile of shit are either morons, totally removed, or liars. Given that the group includes Hammerin' Hank Paulson, Helicopter Ben Bernanke, Glorified Jamie Dimon, and Ken Dancing Fool Lewis, I'm going to have to guess that it's some combination of the latter two choices plus some willful self dilusion. If it is not clear to everyone that we are facing an epic financial crisis triggered by loose credit on assets at inflated prices in virtually every asset class, then it will never be clear.

In the past WEEK, we have seen Fannie and Freddie merged with the US Gov't (heretofore Treasie Mae and Feddie Mac), Lehman's effective failure, allegations that AIG needs to raise $30 to $40 billion in order to avoid a "severe credit downgrade", Merrill Lynch gathering some taint, and Washington Mutual approaching the edge. And the US stock market barely budged from last Friday's close to this past Friday. Down a smidge, but not much.

[See NY Times article on Lehman and AIG here]

At some point, people are going to realize that a persistently dwindling availability of credit and that credit which is available is only at more expensive prices (gov't subsidies not withstanding - GSEs) is extremely bad for asset prices of all kinds. When we begin a society where valuations are predicated on attractive returns to an all over primarily all equity buyer, we will have achieved a real bottom. Until then, I think we should remain a bit worried.

The coming week should be exciting.

Honestly, the guys who were trying to sell us this pile of shit are either morons, totally removed, or liars. Given that the group includes Hammerin' Hank Paulson, Helicopter Ben Bernanke, Glorified Jamie Dimon, and Ken Dancing Fool Lewis, I'm going to have to guess that it's some combination of the latter two choices plus some willful self dilusion. If it is not clear to everyone that we are facing an epic financial crisis triggered by loose credit on assets at inflated prices in virtually every asset class, then it will never be clear.

In the past WEEK, we have seen Fannie and Freddie merged with the US Gov't (heretofore Treasie Mae and Feddie Mac), Lehman's effective failure, allegations that AIG needs to raise $30 to $40 billion in order to avoid a "severe credit downgrade", Merrill Lynch gathering some taint, and Washington Mutual approaching the edge. And the US stock market barely budged from last Friday's close to this past Friday. Down a smidge, but not much.

[See NY Times article on Lehman and AIG here]

At some point, people are going to realize that a persistently dwindling availability of credit and that credit which is available is only at more expensive prices (gov't subsidies not withstanding - GSEs) is extremely bad for asset prices of all kinds. When we begin a society where valuations are predicated on attractive returns to an all over primarily all equity buyer, we will have achieved a real bottom. Until then, I think we should remain a bit worried.

The coming week should be exciting.

Tuesday, September 09, 2008

Lehman on the Brink

First off, I'll say that the odds of Lehman making it to next Monday bearing semblance to its current self are 50:50, at best. Honestly, they are probably lower than that. As the old Wall Street adage goes (paraphrasing), "once you have to defend your financial reputation, you have lost it." Tomorrow at 7:30, Lehman appears prepared to vigorously defend its financial reputation after its 50+% stock price decline from yesterday's early morning peak (immediately after the GSE bailout) of $17.40 or so to today's close of seven dollars and change ($7.79).

First off: wow.

Second off: honestly, wasn't it so obvious that Lehman was in trouble as soon as Bear went down? Aren't they the next logical domino?

I emailed my Little Brother (LB) today when Lehman was somewhere around ten bucks and said, "this feels a lot like March 14th." If you read the email I sent around on March 16th about 30 minutes before Bear was purchased (though penned hours before), so much of the same applies. If you haven't read that post, and I suspect you haven't, please take a few minutes to do so.

If you are a hedge fund manager, it's been a rough year. Long days, sleepless nights. The volatility seems unending. Huge commodity rally. Huge commodity collapse. Financials just keep trending down, but occasionally interspersed are "12 sigma" rallies in the sector. Seems like everyday has been some new pain. Well, let me tell you what ails Johnny Hedge Fund Manager today: he is being pinged by client after client with the following simple question: "what is your counterparty and prime brokerage exposure to Lehman?" Let me tell you what he wants to answer: "zero exposure." Worst case, his response is, "we have some modest amount of exposure that we are in the process of unwinding."

There goes Lehman's liquidity. An institutional run on the bank. Again, I will state: IT DOES NOT MATTER THAT FEDDIE MAC OR TREASIE MAE ARE PROVIDING LIQUIDITY TO LEHMAN, NOBODY IS GETTING PAID TO TAKE LEHMAN COUNTERPARTY EXPOSURE. IN SOME SENSE, HEDGE FUND MANAGERS, ET AL, ARE GETTING PAID TO NOT TAKE LEHMAN EXPOSURE.